Alleviating poverty with minimal carbon emission is at the heart of climate-resilient development. This need is particularly acute in South Asia, where the continuing expansion of irrigation holds the promise of pulling smallholders out of poverty but will also result in significant increases in carbon emissions due to overwhelming dependence on fossil fuel-based

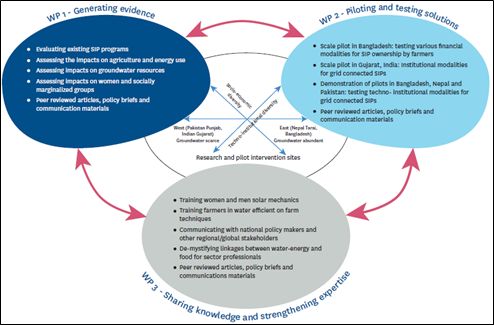

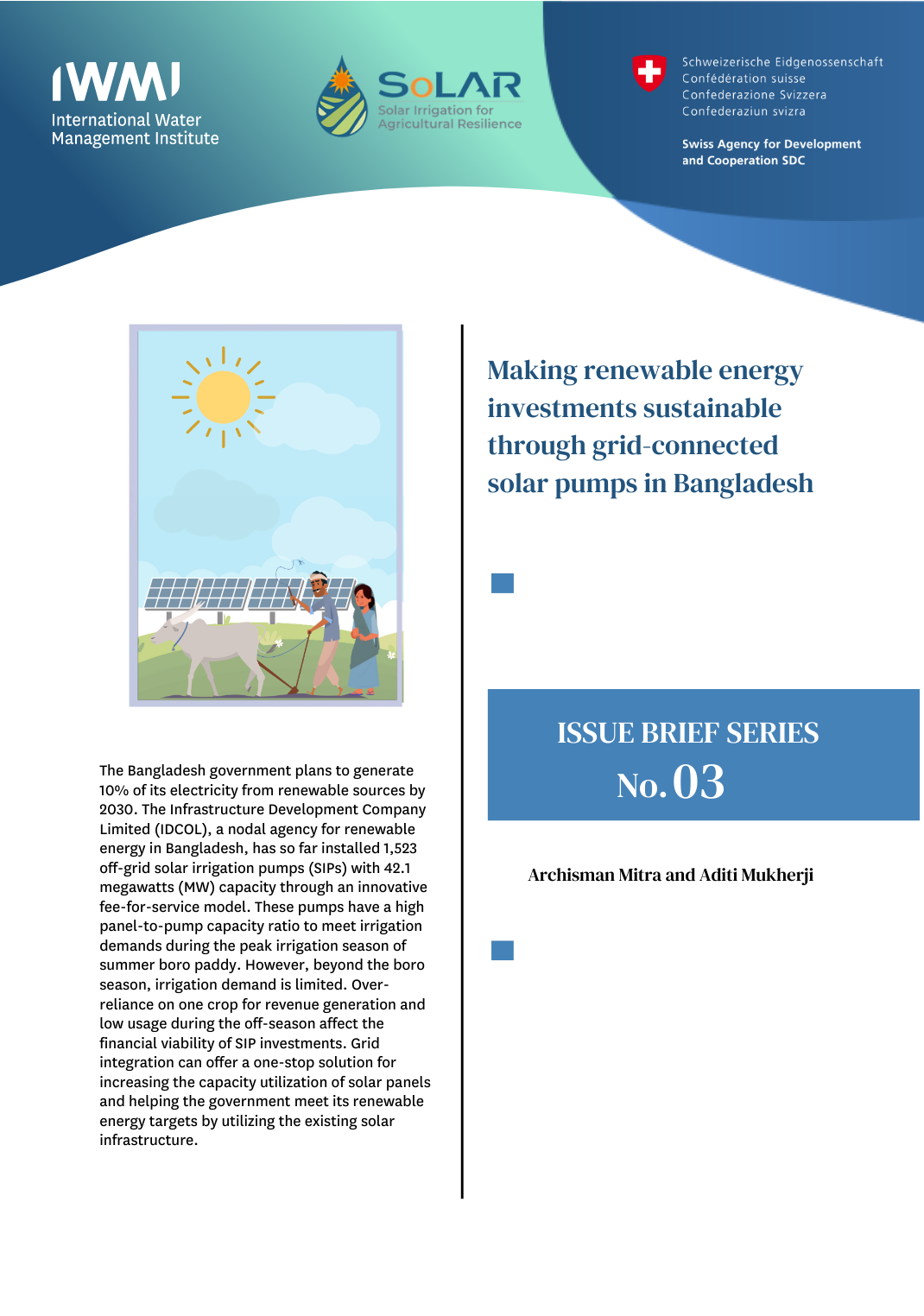

groundwater pumping. Solar irrigation pumps (SIPs) offer a ‘climate-resilient’ solution. IWMI, with support from the Swiss Agency for Cooperation and Development (SDC), is leading a four-year project titled “Solar Irrigation for Agricultural Resilience in South Asia” (SoLAR). The project’s primary goal is to contribute to climate-resilient, gender-equitable, and socially inclusive (GESI) agrarian livelihoods in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan by supporting government efforts to promote solar irrigation. The three main components: generate evidence, develop and test pilot field interventions, and knowledge sharing and capacity building of stakeholders for climate-resilient, GESI-based and groundwater-responsive solar irrigation practices and policies, as shown below.

Like most other projects, the ongoing pandemic slowed down the pace of our work. However, despite several setbacks, our team of researchers and partners have carried out fieldwork in all SoLAR sites and gathered evidence on the impacts of SIPs on four critical parameters – mitigation, adaptation, equity and groundwater use.

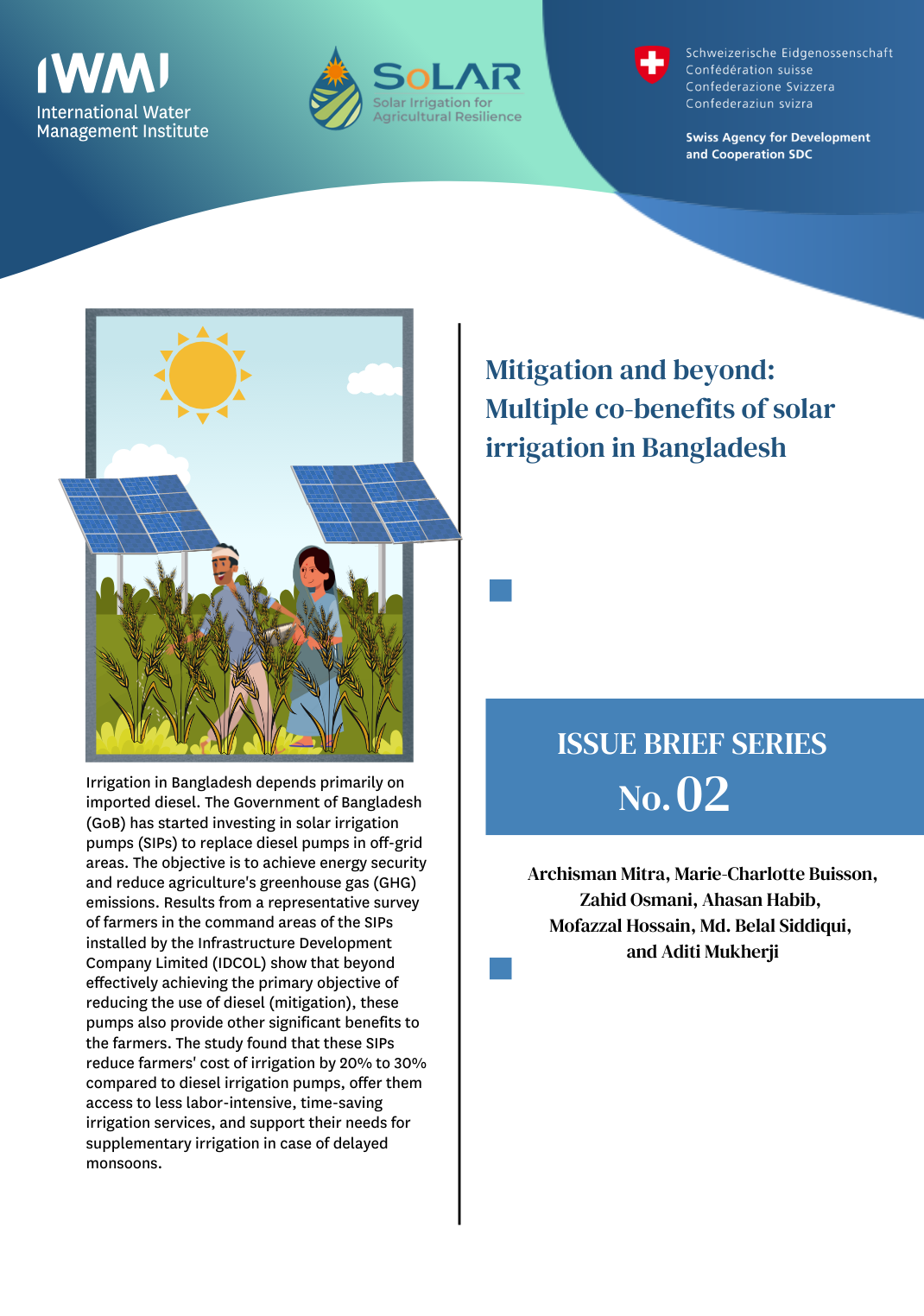

SIPs are a sure win for mitigation

Existing research has already shown that SIPs help reduce carbon emissions. For example, Rajan et al. 2020 show that groundwater irrigation accounts for 8-11% of India’s carbon emissions, while another study undertaken as a part of the SoLAR project shows the 10 million or so diesel pumps in Indo-Gangetic Plains release 12-24 gigatons of black carbon into the atmosphere. Our ongoing work in Nepal found that SIP owners prefer solar pumps (750 hours) over diesel pumps (250 hours) for irrigation when both are accessible. Elsewhere, in Gujarat, we found that 4000 plus farmers using SIPs through the government of Gujarat’s Suryashakti Kisan Yojana (SKY) have replaced their electric pumps with SIPs resulting in a net reduction in carbon emissions and irrigation costs. Diesel pumps are yet to be fully replaced as they act as a backup when SIPs break down or during stretches of foggy days with low solar output. They are also used for irrigating plots not served by SIPs, given the high degree of land fragmentation.

A wide array of solar panels at the Mahakali SKY feeder, Mehsana district, Gujarat, India

Photo: Zeba Ahsan/IWMI

SIPs help in climate change adaptation and vulnerability reduction, but the evidence is mixed

Evidence from our research sites show that SIPs contribute to climate change adaptation and vulnerability reduction in three ways. Firstly, SIPs help hedge against rainfall variability. Farmers in our region are experiencing longer gaps between two rainfall events during the monsoon. While monsoon crop has traditionally been rainfed, irrigation application during the season is rising, with SIPs being used for supplemental irrigation in the monsoon. For example, we found that almost 95% of SIPs operated by IDCOL’s (Infrastructure Development Company Limited) sponsors in the Khulna district of Bangladesh provided irrigation for aman paddy grown in the monsoon season. The second pathway of adaptation is through crop diversification, whichis often promoted as a climate adaptation strategy. We find mixed evidence. In our sites in Bangladesh, farmers who get water from SIP devote a larger share of their land to water-intensive boro paddy, while diesel farmers have more diversified cropping systems.

In contrast, in our sites in Nepal, we find that SIP farmers diversify their cropping patterns and grow more vegetables than their diesel counterparts. The third pathway for vulnerability reduction is through increased farm profits and incomes after adopting SIPs. In Gujarat, almost 50% of farmers who enrolled under the SKY program received payment from the sale of electricity to the grid. In Nepal and Pakistan, farmers with access to SIP devoted a larger share of their land to high-value crops like vegetables and orchards. As a result, they earned a higher income than farmers without access to irrigation from SIPs. Reduced use of diesel also reduced costs of cultivation for SIP farmers. We hope to work further and strengthen the evidence base on the role of SIPs in adaptation and vulnerability reduction in South Asia.

Image showing solar panels and a dug well at village Baharke Sargaane, Hafizabad district, Pakistan

Photo: Haris Sagheer Bhatti/IWMI

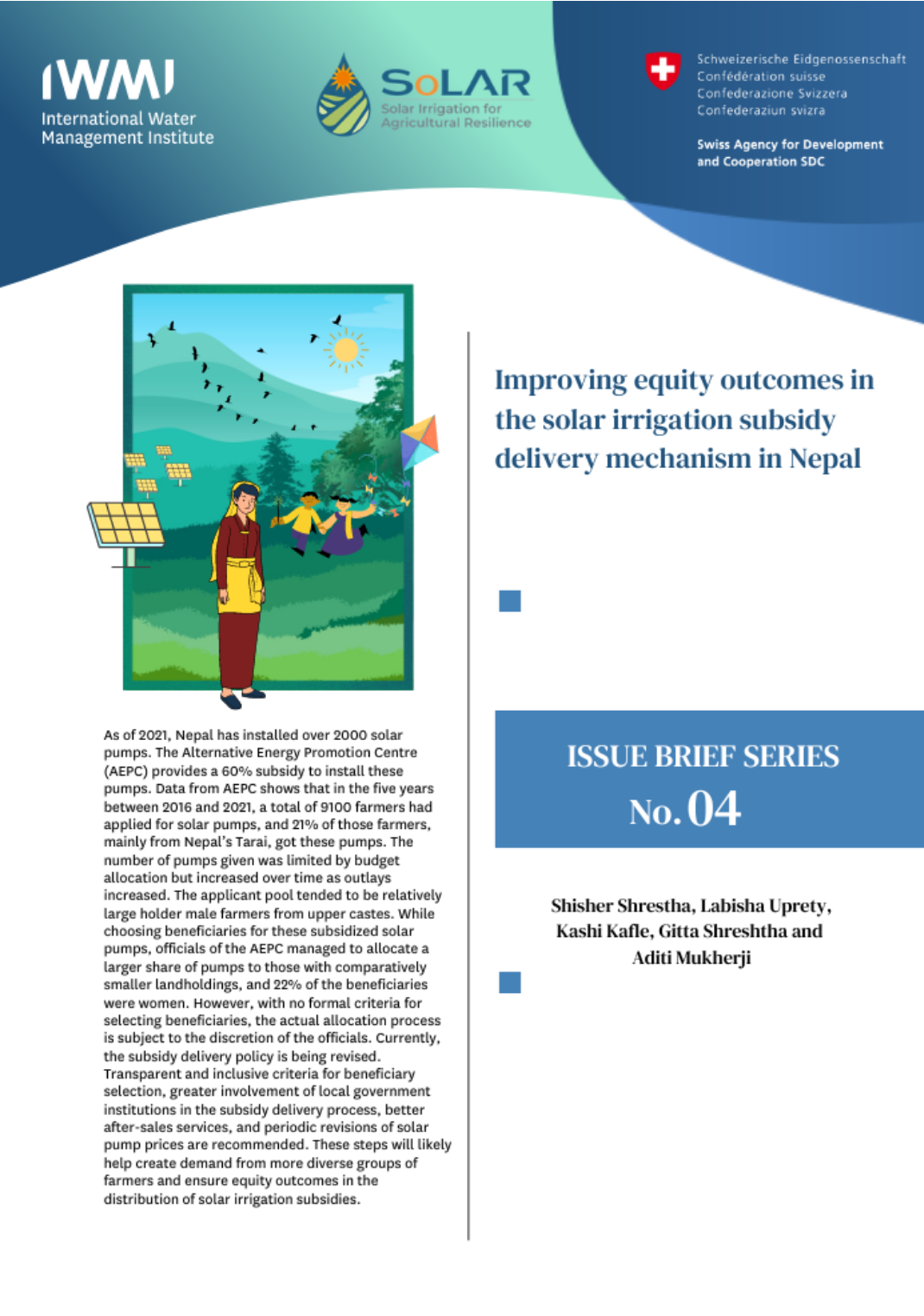

Equity and gender outcomes of SIP adoption are important but not well understood and often mixed

Not many agencies in South Asia pay explicit attention to gender and equity dimensions while implementing solar irrigation programs. One exception is Nepal’s AEPC (Alternative Energy Promotion Centre) which consciously employed a gender, equity and social inclusion (GESI) lens while choosing recipients of their subsidized SIPs. For example, they allocated SIPs to smallholders and women farmers in proportions higher than their application share. Yet, the process of collecting applications conducted through private sector involvement meant that the applicant pool was disproportionate from larger farmers. However, AEPC was able to prioritize relatively smallholder farmers from among that pool. In Bangladesh, IDCOL supported SIPs that provided irrigation services to many sharecroppers. In contrast, in the SKY scheme in Gujarat, most of the farmers who opted for solarization happened to be larger farmers who could pay upfront costs.

A woman farmer with her Solar Irrigation Pump (SIP) in Saptkoshi municipality, Saptari district of Nepal

Photo: Nabin Baral/IWMI

Does SIP lead to more groundwater extraction? A million-dollar question that needs urgent evidence

It is often assumed that deployment of SIPs will lead to more groundwater extraction because of zero marginal costs of pumping. Yet, there is little actual evidence to support or reject this hypothesis. One of our major expected outputs from the SoLAR project is understanding how SIPs affect groundwater use. Unfortunately, our groundwater research component, which needed a lot of field instrumentation and measurements, was delayed due to Covid-19. However, we do have indirect evidence from household surveys. In Nepal, two matching groups of farmers (matched on observables using propensity score matching), one with access to SIPs and one without SIPs, were found to apply similar numbers and hours of irrigation for major crops. In India, SKY farmers do not seem to have altered their cropping patterns after the solarization of pumps, possibly implying no change in groundwater used for irrigation. Our team is conducting detailed field measurements on groundwater use among SIP and non-SIP farmers in Bangladesh and Indian Gujarat.

Dr Aditi Mukherji, Director, Climate Change Impact Platform, CGIAR